Background and History of Subnet Masks

Subnet masks were officially introduced to the TCP/IP protocol stack through RFC 950 in 1985 as an innovative technology to solve the serious inefficiency problems of the early internet’s classful addressing system. In the early 1980s, the internet used the A, B, C class system. Class A was identified by the first byte (1-126) supporting approximately 16 million hosts, Class B by the second byte (128-191) supporting approximately 65,000 hosts, and Class C by the third byte (192-223) supporting 254 hosts. This rigid structure caused critical problems. Organizations needing 1,000 hosts had to be allocated Class B (65,534) as Class C (254) was insufficient, wasting over 64,000 IP addresses. Conversely, organizations needing only 300 hosts had to be allocated an entire Class C (254), offering no flexibility. Subnet masks emerged to solve this inefficiency by enabling division of one network into multiple small subnetworks (subnets), allowing arbitrary adjustment of boundaries between network and host portions to precisely allocate the required number of hosts, forming the foundation for CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Routing) introduction in 1993 and becoming a core concept of modern internet address management.

Structure and Principles of Subnet Masks

Subnet masks consist of 32 bits (4 octets) like IP addresses and have binary patterns of consecutive 1s followed by consecutive 0s. Bits set to 1 represent the network portion, which must have identical values for all hosts within that network, while bits set to 0 represent the host portion, allowing each host to have unique values. For example, 255.255.255.0 in binary is 11111111.11111111.11111111.00000000, where the first 24 bits (three octets) are the network portion and the last 8 bits (one octet) are the host portion, providing 256 (2^8) addresses with 254 hosts allocatable excluding network and broadcast addresses. 255.255.255.128 in binary is 11111111.11111111.11111111.10000000, with 25 bits for network and 7 bits for host portions, providing 128 (2^7) addresses with 126 hosts. 255.255.255.192 in binary is 11111111.11111111.11111111.11000000, with 26 network bits and 6 host bits providing 64 (2^6) addresses with 62 hosts. Subnet masks must start with consecutive 1s and end with consecutive 0s. Patterns like 11111111.11111111.11111111.11001100 (255.255.255.204) with mixed 1s and 0s are invalid, as this is an essential condition for routing efficiency and standard compliance.

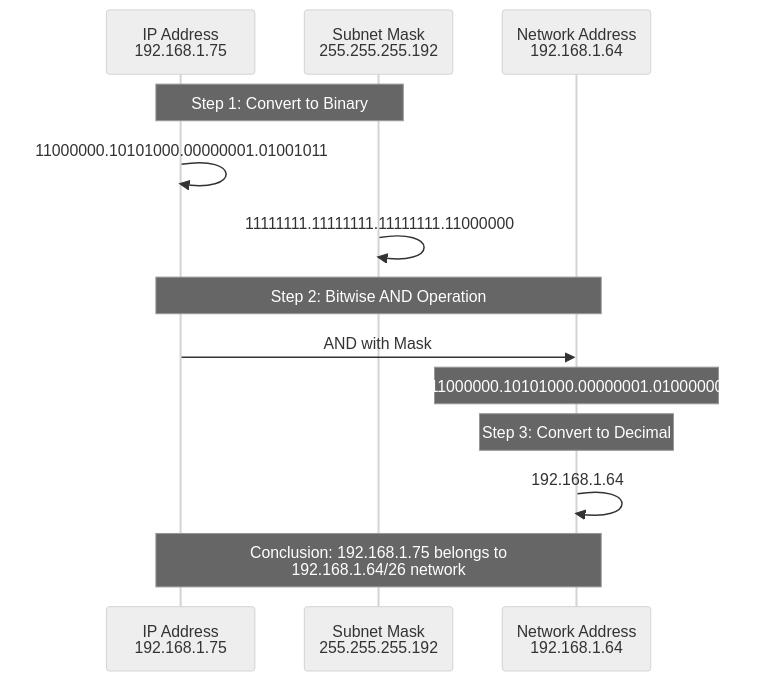

AND Operation Principles of Subnet Masks

The core operating principle of subnet masks is bitwise AND operation. After converting IP addresses and subnet masks to binary, AND operations are performed at each bit position to extract network addresses, enabling determination of whether two IP addresses belong to the same network and routing decisions. AND operation rules are logical operations where the result is 1 only when both bits are 1, with all other cases resulting in 0, following the truth table: 1 AND 1 = 1, 1 AND 0 = 0, 0 AND 1 = 0, 0 AND 0 = 0. For a concrete example of AND operation between IP address 192.168.1.75 and subnet mask 255.255.255.192 (/26): first, converting 192.168.1.75 to binary gives 11000000.10101000.00000001.01001011; converting subnet mask 255.255.255.192 to binary gives 11111111.11111111.11111111.11000000; performing bitwise AND operation gives 11000000.10101000.00000001.01000000; converting to decimal gives 192.168.1.64 as the network address. Through this operation, 192.168.1.75 belongs to the 192.168.1.64/26 network, with address range 192.168.1.64 ~ 192.168.1.127 (64 addresses), network address .64, broadcast address .127, and usable host addresses .65 ~ .126 (62 hosts).

Major Subnet Mask Values and Use Cases

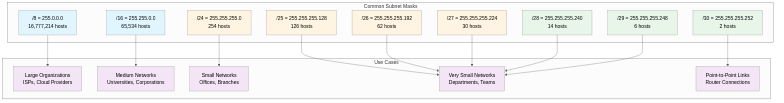

Class A-based Subnet Masks

255.0.0.0 (/8) is Class A’s default subnet mask with 8-bit network and 24-bit host portions, providing 16,777,216 (2^24) addresses with 16,777,214 hosts allocatable. It is primarily used by large ISPs (Internet Service Providers), cloud service providers (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure), global corporations, and government agencies. For example, 10.0.0.0/8 is a private IP range widely used in large-scale corporate internal networks. 255.128.0.0 (/9) supports 8,388,606 hosts, 255.192.0.0 (/10) supports 4,194,302 hosts, 255.224.0.0 (/11) supports 2,097,150 hosts, and 255.240.0.0 (/12) supports 1,048,574 hosts, used for dividing Class A into smaller blocks, useful for allocating IP blocks by region or department within large organizations.

Class B-based Subnet Masks

255.255.0.0 (/16) is Class B’s default subnet mask with 16-bit network and 16-bit host portions, providing 65,536 (2^16) addresses with 65,534 hosts allocatable. It is primarily used by medium-to-large universities, corporate headquarters, data centers, and government ministries. For example, 172.16.0.0/16 is a private IP range used for corporate internal networks. Subnet masks from /17 to /23 provide varying host counts (/17: 32,766 hosts, /23: 510 hosts), used for subdividing Class B into multiple subnets, efficiently allocating IPs according to actual host needs through VLSM (Variable Length Subnet Mask).

Class C-based Subnet Masks

255.255.255.0 (/24) is Class C’s default subnet mask with 24-bit network and 8-bit host portions, providing 256 (2^8) addresses with 254 hosts allocatable. It is most commonly used in small offices, branches, departments, and home networks. For example, 192.168.1.0/24 is widely used as the default setting for home routers. 255.255.255.128 (/25) supports 126 hosts for dividing /24 networks into two subnets, 255.255.255.192 (/26) supports 62 hosts for four subnets, 255.255.255.224 (/27) supports 30 hosts for eight subnets, 255.255.255.240 (/28) supports 14 hosts for sixteen subnets, 255.255.255.248 (/29) supports 6 hosts for thirty-two subnets, and 255.255.255.252 (/30) supports 2 hosts for sixty-four subnets. /30 is primarily used for Point-to-Point connections between routers (WAN links, BGP peering).

Relationship Between Subnet Masks and CIDR Notation

With CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Routing) introduction in 1993, subnet masks began to be expressed using slash notation, concisely representing the number of network bits in /n format, greatly improving readability and convenience. CIDR notation and subnet masks correspond one-to-one: /8 is 255.0.0.0 (8-bit network, 24-bit host), /16 is 255.255.0.0 (16-bit network, 16-bit host), /24 is 255.255.255.0 (24-bit network, 8-bit host), /25 is 255.255.255.128 (25-bit network, 7-bit host), /26 is 255.255.255.192 (26-bit network, 6-bit host), /27 is 255.255.255.224 (27-bit network, 5-bit host), /28 is 255.255.255.240 (28-bit network, 4-bit host), /29 is 255.255.255.248 (29-bit network, 3-bit host), and /30 is 255.255.255.252 (30-bit network, 2-bit host). CIDR notation advantages include concise notation (192.168.1.0/24 instead of 192.168.1.0 255.255.255.0), intuitive calculation (/24 immediately indicates 8 host bits = 2^8 = 256 addresses), widespread adoption as international standard for network configuration, routing tables, and documentation, and support for VLSM and route aggregation enabling flexible network design.

Subnet Mask Calculation Practice

Calculating Subnet Mask from Host Count

The method to calculate the appropriate subnet mask given required host count is as follows: first, add 2 to the required host count (reserved for network and broadcast addresses); next, find the smallest power of 2 that equals or exceeds this value; the exponent of that power becomes the number of host bits; finally, subtract the host bits from 32 to get the network bits (CIDR prefix). For example, if 50 hosts are needed: 50 + 2 = 52, smallest power of 2 above is 2^6 = 64, so 6 host bits are needed, 32 - 6 = 26, so /26 (255.255.255.192) is required providing 62 usable hosts. For 100 hosts: 100 + 2 = 102, 2^7 = 128, so 7 host bits needed, /25 (255.255.255.128) required providing 126 hosts. For 500 hosts: 500 + 2 = 502, 2^9 = 512, so 9 host bits needed, /23 (255.255.254.0) required providing 510 hosts.

Subnet Division Calculation

To divide a 192.168.1.0/24 network into 4 equal-sized subnets: 4 subnets require 2 additional bits (2^2 = 4), adding 2 to /24 gives /26, /26 subnet mask is 255.255.255.192, and each subnet has 64 addresses (62 usable hosts). The four subnets are: first 192.168.1.0/26 (192.168.1.0 ~ 192.168.1.63, usable: .1 ~ .62), second 192.168.1.64/26 (192.168.1.64 ~ 192.168.1.127, usable: .65 ~ .126), third 192.168.1.128/26 (192.168.1.128 ~ 192.168.1.191, usable: .129 ~ .190), fourth 192.168.1.192/26 (192.168.1.192 ~ 192.168.1.255, usable: .193 ~ .254).

Checking if Two IPs are in Same Network

To check if 192.168.1.75 and 192.168.1.130 belong to the same network with subnet mask 255.255.255.192 (/26): first, 192.168.1.75 AND 255.255.255.192 = 192.168.1.64; second, 192.168.1.130 AND 255.255.255.192 = 192.168.1.128; since the two network addresses differ (192.168.1.64 ≠ 192.168.1.128), the two IPs belong to different networks and cannot communicate directly, requiring a router.

Real-World Applications of Subnet Masks

Enterprise Network Design

When a small-to-medium enterprise is allocated a 192.168.0.0/16 private IP block and uses VLSM for efficient network design: headquarters with 200 employees receives 192.168.0.0/24 (254 hosts), Branch A with 50 employees receives 192.168.1.0/26 (62 hosts), Branch B with 30 employees receives 192.168.1.64/27 (30 hosts), server farm with 20 machines receives 192.168.1.96/27 (30 hosts), DMZ web servers with 5 machines receive 192.168.1.128/29 (6 hosts), Point-to-Point router links receive 192.168.1.136/30, 192.168.1.140/30 (2 hosts each), with remaining address space reserved for future expansion.

Cloud Environment (AWS VPC)

Creating AWS VPC with 10.0.0.0/16 and structuring using subnet masks: Public Subnet A uses 10.0.1.0/24 (254 hosts, web servers, load balancers), Public Subnet B uses 10.0.2.0/24 (254 hosts, different availability zone for high availability), Private Subnet A uses 10.0.10.0/24 (254 hosts, application servers), Private Subnet B uses 10.0.11.0/24 (254 hosts, high availability), Database Subnet A uses 10.0.20.0/24 (254 hosts, RDS, ElastiCache), Database Subnet B uses 10.0.21.0/24 (254 hosts, high availability), with remaining address space (10.0.30.0/24 ~ 10.0.255.0/24) reserved for future service expansion.

Home Network

Typical home router subnet mask usage: uses 192.168.1.0/24 (255.255.255.0) network, router gateway uses 192.168.1.1, DHCP range set to 192.168.1.100 ~ 192.168.1.200 (dynamic allocation), static IPs 192.168.1.10 ~ 192.168.1.50 (servers, NAS, printers), reserved addresses 192.168.1.201 ~ 192.168.1.254 (future use), allowing 254 devices sufficient for typical homes.

Subnet Mask Troubleshooting

Incorrect Subnet Mask Configuration

Incorrect subnet mask configuration causes network communication failures. For example, if the actual network is 192.168.1.0/24 but a host is configured with 255.255.0.0 (/16) instead of 255.255.255.0, the host recognizes 192.168.0.0 ~ 192.168.255.255 as the local network. When communicating with 192.168.2.10, it sends direct ARP requests without going through the router, but since it’s actually a different network, there’s no response and communication fails. Symptoms include normal same-subnet communication but failed different-subnet communication, excessive unnecessary ARP table entries, degraded network performance, and increased broadcast traffic. Solutions include correcting the host’s subnet mask (Windows: ncpa.cpl → adapter properties, Linux: /etc/netplan/ or nmcli), verifying DHCP server configuration distributes correct subnet masks, and reviewing network device (router, switch) settings to ensure VLAN and subnet alignment.

Communication Failure from Subnet Mismatch

When hosts using different subnet masks coexist on the same physical network, communication problems occur. For example, when Host A is 192.168.1.10/24 (255.255.255.0) and Host B is 192.168.1.20/26 (255.255.255.192), Host A recognizes 192.168.1.0 ~ 192.168.1.255 as local but Host B recognizes only 192.168.1.0 ~ 192.168.1.63 as local, causing asymmetric routing. When Host A sends packets to Host B, it communicates directly via ARP, but when Host B responds to Host A (192.168.1.10), it attempts to send through the gateway, making communication unstable. Solutions include standardizing all hosts to use the same subnet mask, using DHCP to automatically distribute consistent network configuration, clearly managing subnet allocation plans through network documentation, and performing regular network audits to detect mismatches early.

Subnet Boundary Violation

When subnetting, if boundaries don’t align on powers of 2, routing problems occur. For example, setting 192.168.1.50/26 as a subnet: /26 size is 64 so it must start at 0, 64, 128, 192, but 50 is not a valid starting address. The router cannot properly recognize this subnet or add it to the routing table, causing complete network communication failure. Solutions include verifying subnet starting addresses are multiples of subnet size (e.g., /26: 0, 64, 128, 192), using online subnet calculators for validation, establishing and documenting subnet allocation plans during network design, and verifying routing tables after router configuration to ensure subnets are correctly registered.

Advantages and Limitations of Subnet Masks

Advantages

The biggest advantage of subnet masks is improved IP address allocation flexibility, overcoming classful system rigidity to precisely allocate the required number of hosts. Needing 100 hosts allows allocating /25 (126) to minimize waste, and VLSM enables simultaneous use of different-sized subnets within one network. Enhanced network security is also important, reducing broadcast domains by separating subnets to prevent broadcast storms and improve network performance, separating networks by department or function to apply firewall rules and strengthen access control, and limiting damage scope to affected subnets during security breaches to prevent spread across entire networks. Increased routing efficiency is another advantage, enabling routers to quickly calculate network addresses and determine optimal paths through subnet masks, implementing hierarchical network structures to reduce routing table size, and consolidating multiple subnets into single routing entries through route aggregation. Network management convenience is improved, allowing logical subnet division to design networks matching organizational structure or geographic location, easily isolating and diagnosing problematic subnets during troubleshooting, and adding new subnets while maintaining existing structure during network expansion.

Limitations

Subnet mask limitations appear as increased complexity. Understanding binary operations and bit manipulation is required, raising the learning curve for network administrators. Subnet division calculations are complex and prone to mistakes, especially in VLSM environments where multiple subnet sizes coexist making management difficult. Configuration error possibilities are also problematic, as incorrect subnet mask settings cause complete or partial network communication failures making root cause identification difficult, subnet boundary violations cause routing problems, and inconsistent subnet mask usage causes asymmetric routing. It is not a fundamental solution to IPv4 address depletion, as subnet masks only improve IP address utilization efficiency while 32-bit address space limitations still exist. The ultimate solution is transitioning to IPv6 (128-bit address space), but in the current situation where IPv4 and IPv6 coexist, subnet masks continue to be used as core technology for IPv4 network management. Compatibility issues exist, as some old network equipment doesn’t support CIDR and VLSM requiring upgrades to modern protocols, legacy applications assume classful addressing and may malfunction in CIDR environments, and subnet mask notation between different vendors’ equipment can subtly differ requiring caution during integration.

Conclusion

Subnet masks have been a core component of TCP/IP networking for nearly 40 years since introduction through RFC 950 in 1985, solving classful addressing inefficiency to greatly improve IP address allocation flexibility and enabling logical network division to simultaneously improve security, performance, and management efficiency. The core principle of bitwise AND operation is essential for routers to quickly calculate network addresses and determine optimal paths when forwarding packets, forming the foundation of modern internet routing. With CIDR introduction in 1993 adding slash notation, readability and convenience greatly improved, and through VLSM, simultaneous use of various-sized subnets within one network became possible to maximize IP address utilization. Deep understanding of subnet masks enables establishing efficient subnet allocation plans matching organizational structure and requirements during network design, quickly identifying and resolving communication failure causes during troubleshooting, correctly configuring networks in cloud environments (AWS VPC, Azure VNet, GCP VPC), designing access control and firewall rules by subnet when establishing security policies, and understanding operating principles of routing protocols (OSPF, EIGRP, BGP). Even with IPv6 transition underway, IPv4 is still widely used, and subnet masks will continue to play an important role as indispensable technology for efficiently managing IPv4 networks.